The Johnstown Calamity (1889)

The Johnstown Flood became an event of great national interest. McCullough describes how the Pittsburgh Gazette “was selling its editions so fast that it had to reduce its page size temporarily so as not to run out of paper. Everywhere, people were talking of little else” (204). The coverage was not always factually accurate; for example, the reported death toll initially varied between 100 and 10 000, despite there being “no firsthand facts to go on” at the time (203). Though the inaccuracies were partly due to the difficulty of discerning truth in a disaster’s aftermath, they were also influenced by commercial or political motivations or biases. Many sensational stories emphasized the horror and contained “distortions, wild exaggerations and outright nonsense” (220). These stories seem exploitative in their desire to titillate or entertain rather than inform.

Nevertheless, if an emotional response was the ultimate goal, there may also have been more positive consequences. Johnstown benefited from many charitable donations and was also the first real test of the American Red Cross (229-231). Such stories created villains as well: many of the papers (perhaps rightly) blamed the South Forks Fishing Club, whose millionaire members built the dam for their private resort with perhaps less than stringent standards (246-8). Several papers also described “Huns” (East European immigrants) who stole jewellery off flood victims—anecdotes that were racially prejudiced and untrue (210-212).

Sources and Further Reading:

Allen, Jean. “Remembering Johnstown’s Flood Victims.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 2 Jun. 2002: E2. ProQuest. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

“Johnstown Marks Flood Centennial: City Leaders Say Anniversary Is a Time to Take Pride in Overcoming Adversity.” New York Times 1 Jun. 1989: A18. ProQuest. Web. 5 Jan 2015.

McCullough, David G. The Johnstown Flood. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968. Print.

Walker, James H. The Johnstown Horror!!! or Valley of Death. Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1889. Print. Available on Project Gutenberg

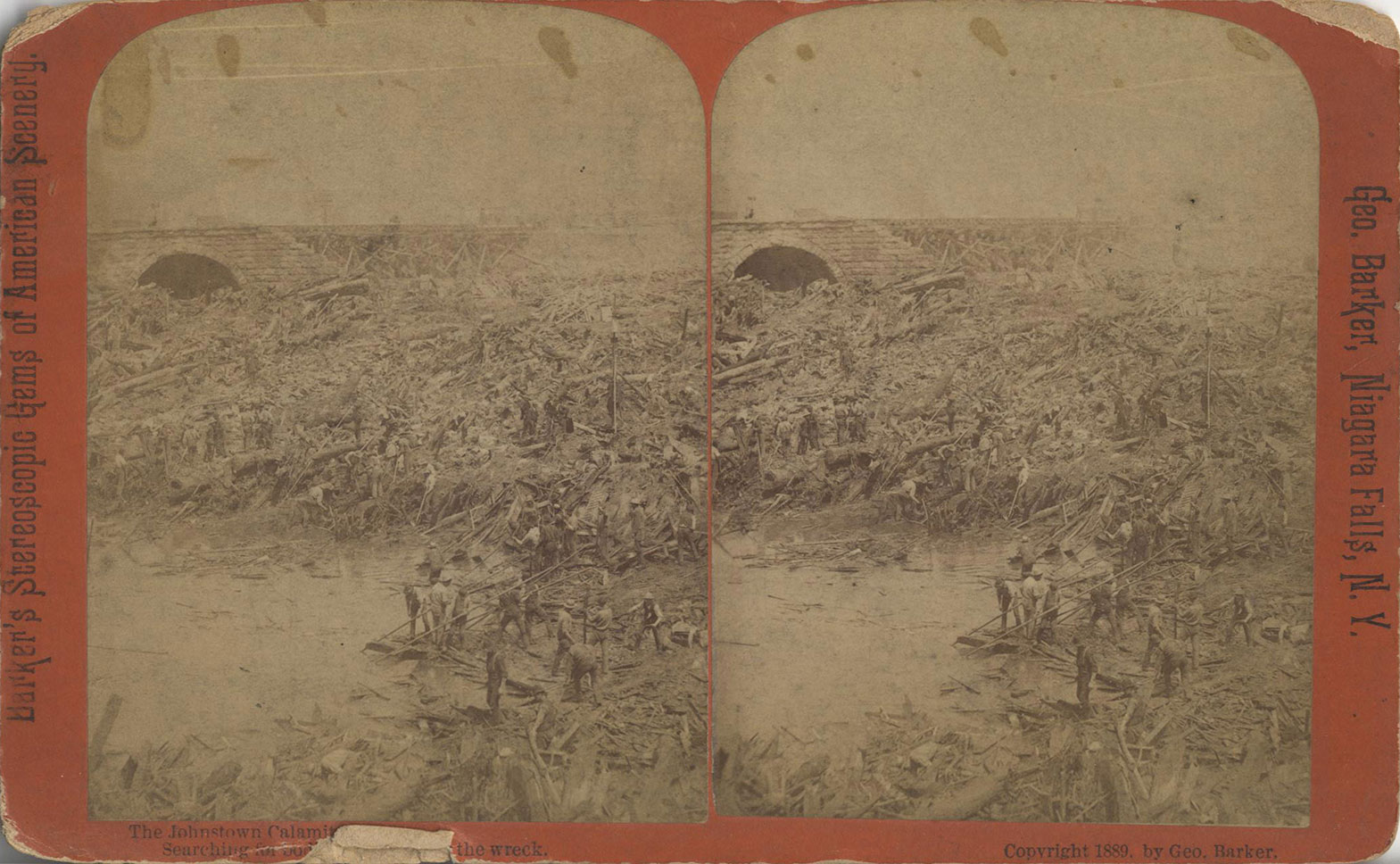

Though Fyfe aligns photography with the slow demise of the catastrophic picturesque (79-80), this stereograph shares some of the same visual characteristics and can be seen as a transitional piece. Several different forms of photography and illustration were popular and co-existed during the 19 th century, such that it is perhaps more useful to think of the period in terms of multiple “photographies” or illustrative techniques rather than in monolithic terms (Clayton 12-22). It is unsurprising that visual media might borrow or appropriate visual techniques from other genres.

The stereograph, for example, was taken from a high vantage point that allows the viewer to survey the damage below—a characteristic that the catastrophic picturesque used to “encourage [viewers] to see illustrations as aesthetic objects, and to examine illustrations of disasters from a safe, contemplative remove” (Fyfe 79-80). Furthermore, if the “blend of scenery and wreckage” characterizes the catastrophic picturesque (Fyfe 81), then the wreckage in this stereograph becomes the scenery. Broken, jumbled, and splintered pieces of wood—alienated from the recognizable objects they once were—are what form the “landscape.” Lastly, Fyfe describes the catastrophic picturesque as a way to reconstruct or even replace the accident as experience (79). Since the picturesque “offer[s] pictures in place if the ‘experience’ they claimed to deliver,” then stereography—whose champions exploited its 3D effect for their experiential claims—is an especially fitting medium for this visual genre.

Sources and Further Reading:

Clayton, Owen. Literature and Photography in Transition, 1850-1915. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.Print.

Fyfe, Paul. “Illustrating the Accident: Railways and the Catastrophic Picturesque in The Illustrated London News.” Victorian Periodicals Review. 46.1 (2013): 61–91. Project MUSE. Web. 20 Feb. 2015. Available online

Although this stereograph may share some aspects of social documentary photography, it does not fit neatly into this category. The stereograph is certainly concerned with the social cost of the disaster: Barker deems the event a “calamity” rather than simply a “flood” and includes human figures in the act of searching for bodies. However, the stereograph is also concerned with nature’s power. It was taken from a relatively high angle and emphasizes the sheer scale of the destruction that dwarves the humans pictured rather than overtly focus on the people themselves. Moreover, it would be difficult to argue the stereograph is committed to humanistic values or that it calls for action—two hallmarks of social documentary photography. It is difficult to speculate about the intent or approach of the photographer. As Rosenblum notes, “in themselves images could not necessarily be counted on to convey specific meanings…how they were perceived often depended on the outlook and social bias of the viewer” (353). As with all media, it is ultimately reductive to ascribe a singular purpose to a work of art at the exclusion of others. But the questions such photographs raised in the 19th century about how documentary purposes, Art or aesthetic ideals, and ethics intersect still persist today.

Sources and Further Reading:

Lindsay, David. “The Kodak Camera Starts a Craze.” PBS.org, n.d. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Web. 5 Jan. 2015. Available online

Newhall, Beaumont. “Documentary Approach to Photography.” Parnassus 10.3 (1938): 3–6. JSTOR. Web. 3 Jan. 2015. Available on JSTOR

Rosenblum, Naomi. A World History of Photography. 4th ed. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 2007. Print.