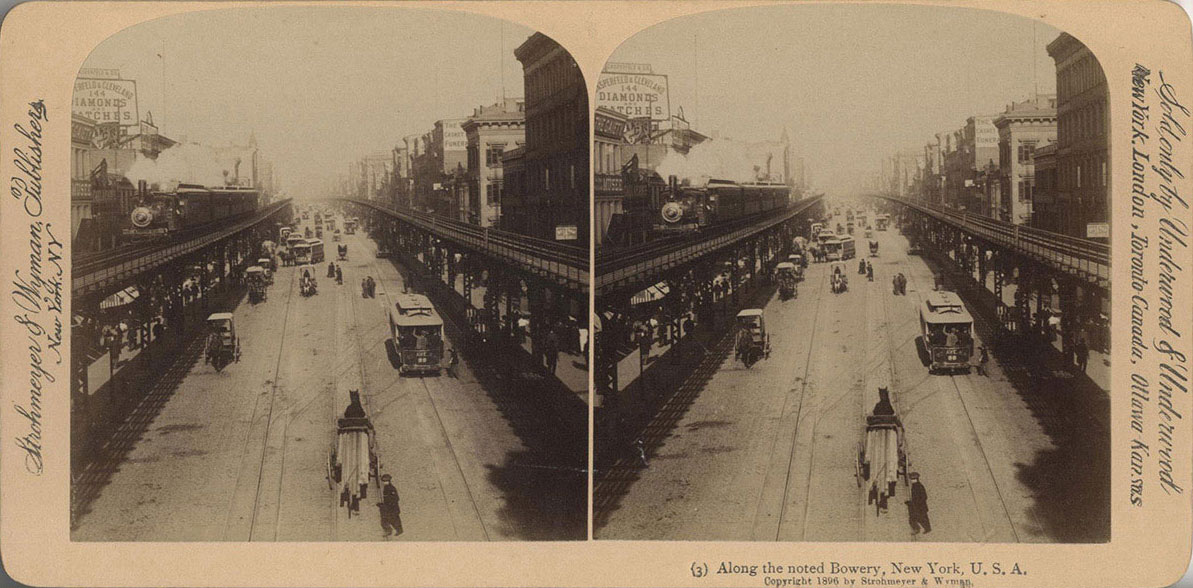

Along the noted Bowery, New York (1896)

New York City’s elevated railway (or “el train”) was a response to congestion and sanitation problems caused by horse-drawn street transportation. Social reformers, such as Dr. Rufus Gilbert, hoped the elevated railway would also relieve extreme overcrowding and poor living conditions in Manhattan’s downtown by allowing the poor to move to more sanitary, less populated areas while still being able to travel to work (Derrick 10-22). The first elevated railway opened to passengers in Manhattan the late 1860s and the system expanded northwards throughout the 1870s (Roess and Sansonne 104-109). The el train allowed middle-class and some working-class New Yorkers to move northwards into less crowded real estate. But despite reformers’ hopes, land expansion and development was not enough to keep pace with New York’s rapidly growing population (Derrick 22), which more than doubled from 1870-1900 (10). New tenements simply sprang up further north (Roess and Sansonne 134) or even clustered around the elevated railway lines (Derrick 32).

In popular visual representation, the railway is often a key component of the “industrial picturesque”—an aesthetic genre that focused on the railway’s “most placid moments and idealized features” (Fyfe 61-2). As an example of this genre, this stereograph uses the straight, receding diagonal lines of the train tracks for both stability in their regularity, as well as dynamism or sense of movement that “underlines the intrinsic power and excitement associated with the railroad itself” (Lyden 47). However, it is also worth noting that the railway in this case is tied to an urban, metropolitan setting while many of the examples that Fyfe cites are not.

In William Dean Howells’ novel, A Hazard of New Fortunes (1890), Basil March, a middle-class literary journalist, takes the 3rd Ave El train down Bowery Street (pictured in the stereograph). He describes the working-class immigrants in the car with him as “unfailingly entertaining as ever”(Howells 182). Like the flâneur, March objectifies the people he sees, eschewing “who and what they individually were” in favour of the physical characteristics he finds so aesthetically pleasing (183). March’s elevated train ride is both a scene of social contact and self-gratifying spectacle as he inspects “the gay ugliness—the shapeless, graceless, reckless picturesqueness of the Bowery” (183). For March, the roughness of the urban crowd does not disrupt or defy the picturesque; rather, they are absorbed and totalized into an ultimately pleasing picture.

Sources and Further Reading:

Derrick, Peter. “Never Enough: The Beginnings of Rapid Transit in New York.” Tunneling to the Future: The Story of the Great Subway Expansion That Saved New York. New York: New York University Press, 2001. 9-46. Print. 5 Nov. 2014.

Fyfe, Paul. “Illustrating the Accident: Railways and the Catastrophic Picturesque in The Illustrated London News.” Victorian Periodicals Review 46.1 (2013): 61-86. Web. 20 Feb. 2015.

Howells, William D. A Hazard of New Fortunes. New York: Modern Library, 2002. Print. Available on Project Gutenberg

Lyden, Anne M. Railroad Vision: Photography, Travel, and Perception. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003. Print.

Roess, Roger P., and Gene Sansone. “To ‘El’ and Back: The Era of the Elevated Railroad.”The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System. Berlin: Springer, 2013. 89-138. Web. 5 Nov. 2014.

In “The Stereoscope and the Miniature,” Pietrobruno argues that stereographs of New York City portrayed the metropolis as “the heart of modern progress and civilization” (181). Many of the features she describes appear in this stereograph. For example, the street “extends to infinity” in the background, making the city appear limitless in power and potential (181). The stereograph celebrates urban technological innovations (e.g. the elevated train and streetcars) as symbols of modernity and progress (183). Taken above street level, the stereograph also promotes an orderly view of the city (182) that omits the problems of overcrowding, poverty, and crime that prevailed in the infamous Bowery District and Five Points slums mere steps away. Furthermore, the photographer took this photograph from the railway platform—thus, industry literally elevates him above those he does and does not choose to photograph.

Bowery Street was “noted” for being the site of poverty, crime, disease, and prostitution. The surrounding area was densely populated—for example, Ward 10, extending just east of Bowery Street, had a population density of 347,749 in 1890 and 433,986 in 1900 (Gardner n.p.). The tenements, low-income housing where almost all of these people lived, were overcrowded, filthy, frequently flooded and poorly-ventilated (Riis 11-12). Deadly disease outbreaks (especially cholera) and fires spread rapidly through the cramped wooden buildings.

Jacob Riis, a social reformer, used photography in How the Other Half Lives (1890) to expose the New York slums and convince authorities and the public of the need for reform. Photography, as a relatively new and realist mode, was inherent to his reformist intentions: writing, he said, “[made] no impression” and drawing “would not have been evidence of the kind I wanted” (Riis 267). Realist photography, by contrast, confronted—and, no doubt, shocked—his middle- and upper-class audiences with the ugly truth. Critics have since questioned whether his photography and writing might have, intentionally or not, encouraged a sense of spectacle or titillation. Nevertheless, Riis’s photography is an interesting counterpoint to the sanitized, touristic view of this stereograph, which is motivated by commercial interests of tourism and marketability rather than a desire for reform.

Sources and Further Reading:

Gardner, Todd. “New York (Manhattan) Wards: Population & Density 1800-1910.” Demographia.com. Demographia, n.d. Web. 13 Nov 2014. Available online

Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. “The stereoscope and the miniature.” Early Popular Visual Culture 9.3 (2011): 171-190. Web. 13 Nov 2014.

Riis, Jacob. How the Other Half Lives. New York: Penguin Books, 1997. Print.

Riis, Jacob. The Making of an American. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1901. Print.