“Fine day, sir, and welcome” (1902)

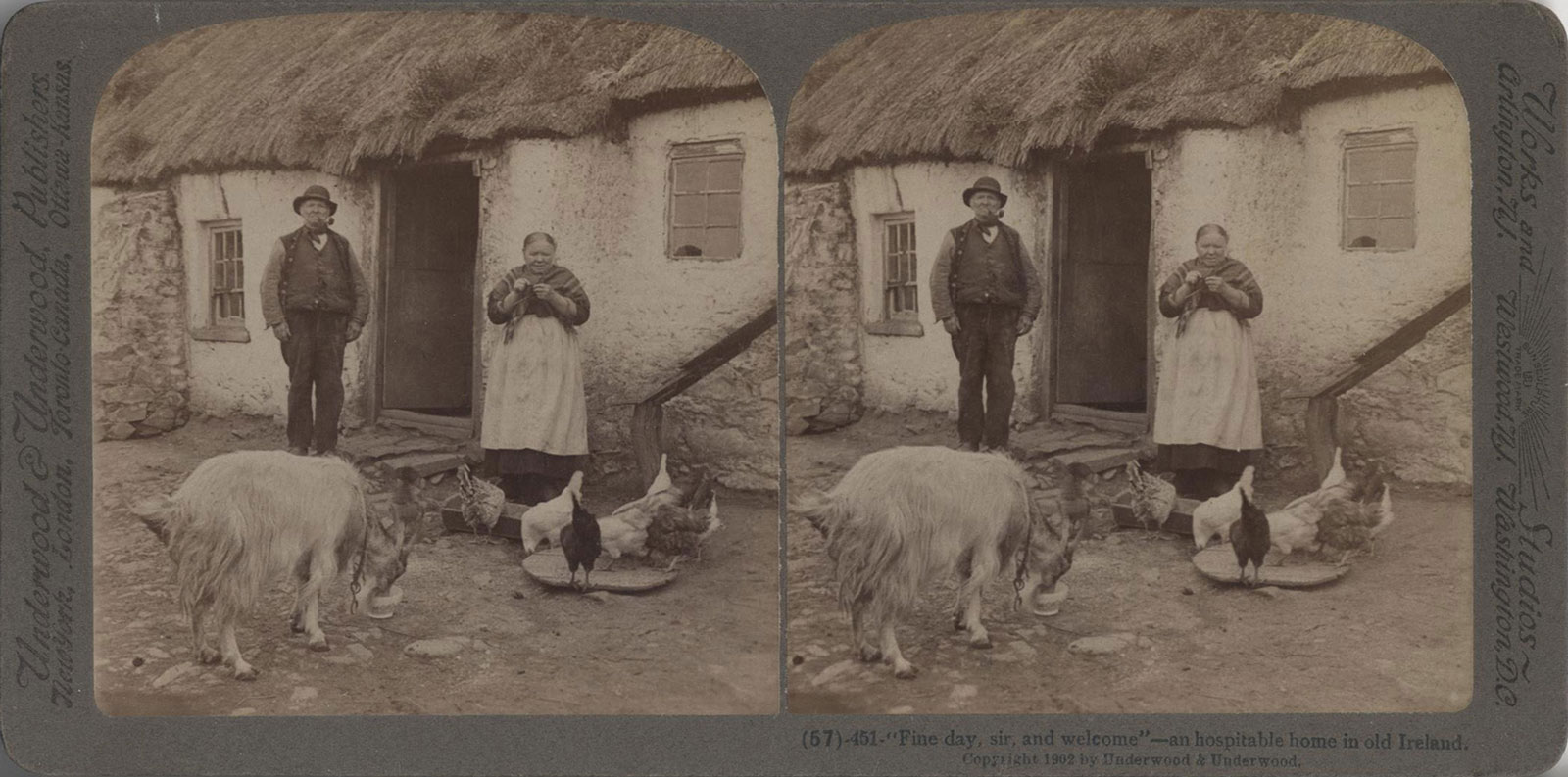

Though Strain discusses photography of Indigenous peoples on the periphery or even outside of the Empire proper, much of her essay still applies to this representation of an Irish couple. Ireland displayed characteristics of a colony in their economic relationship (Ryder 166) and through representation. Strain notes how photographers began to contextualize their subjects “within a lush, natural environment with crudelybuilt shelters” as a way to suppress signs of colonial contact (91-92). One can clearly see these aspects in the stereograph’s rural features, such as the thatched roof and the farm animals. These features depict the Irish as untouched by signs of industrialization or commerce, separating it from the rational, industrialized Imperial centre.

In her essay on (English and Irish) national character, Cullingford discusses how the Irish, because of their skin colour, became a “disturbing mixture of sameness and difference, [of] geographical closeness and cultural distance” to the English (287). English dramatists therefore emphasized characteristics that “signaled political incompetence” in their representations of Irishmen (287). Thus, even as such representations romanticized the rural Irish, they also became “justification” for Irish inferiority and paternalistic Imperial attitudes towards the Irish (287-8). The text on the back of the card signals the couple’s political incompetence through their economic status and illiteracy (notably, these are metrics of capitalism and education established and promoted by the English Imperial centre). For example, the stereo card emphasizes the “unlettered” couple’s constant “fight with poverty.” Their lack of wealth and education render them politically impotent and therefore, in Imperialist thinking, in need of Empire rather than a threat to it.

Sources and Further Reading:

Cullingford, Elizabeth B. “National Identities in Performance: The Stage Englishman of Boucicault’s Irish Drama.” Theatre Journal 49.3 (1997)

287-300. Web. Available online

Ryder, Sean. “Defining Colony and Empire in Early Nineteenth-Century Irish Nationalism.” Was Ireland A Colony? Economics, Politics and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Ireland. Ed. Terrence McDonough. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2005. Print.

Strain, Ellen. “Exotic Bodies, Distant Landscapes.” Wide Angle 18.2 (1996) 70-100. Web. Available online

“If you would like to see the height of hospitality,

The cream of kindly welcome and the core of cordiality;

Joys of old times are you wishing to recall again,

Oh, come down to Donovan’s and there you’ll meet them all again.

Soon as you lift the latch, little ones are meeting you;

Soon as you’re ‘neath the thatch, kindly looks are greeting you;

Scarce have you time to be holding out the fist to them—

Down by the fireside you’re sitting in the midst of them.”

Read Stephen Gwynn: Highways and Byways in Donegal and Antrim; W. M. Thackeray: Irish Sketchbook; Samuel Lover’s Poems and Songs; Kate Douglas Wiggin: Penelope’s Irish Experiences. Read the short stories of Jane Barlow.

“A Fine Day, Sir, and Welcome”: a Hospitable Home in Ireland

[translations into other languages]

Further Reading:

McAuliffe, John. “Taking the Sting out of the Traveller’s Tale: Thackeray’s Irish Sketchbook.” Irish Studies Review 9(1) 25-40. Web. 27 Nov. 2014.

Dictionary of Irish Biography. ed. James McGuire and James Quinn. Web. 27 Nov. 2014.

nicoley133. “Bing sings ‘The Donovans.'” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 7 Oct. 2011. Web. 27 Nov. 2014. Available on YouTube.

The picturesque also contains political or imperialist overtones. As an ideal, the picturesque is a highly subjective experience and therefore privileges the viewer above all else—it centres on the viewer’s pleasure and stimulating his or her imagination. As Andrews notes, tourists of the picturesque often acted like “big-game hunters,” boasting about “‘capturing’ wild scenes, and ‘fixing’ them as pictorial trophies in order to sell them or hang them up in frames” (Andrews qtd. in Hooper 176). In an imperialist context, the picturesque—like the big-game hunter who encounters and conquers savage landscapes—implies objectification, appropriation and ownership of Irish land or peoples. The picturesque’s subjective nature also privileges the viewer’s (read: colonizer’s) impression of a landscape or people over other perspectives.

For example, the narrative on the back of the stereograph omits, simplifies or even romanticizes the political, social and economic reality of Ireland at the time. For example, the travel guide mentions the couple’s “fight with poverty” and “worries and sorrows, not a few.” This could be a reference to recurring famines or agricultural depression that sparked the Land War, a period of civil unrest and clashes between land owners and tenants in the late 19 th century (Adelman and Pearce 79-84). However, their troubles are simplified and offered as a reason that their “cheery” “Irish temperament” is all the more admirable. This is similar to Alfred Austin’s narrative of his Irish travels, which offered a “sheltered image” of Ireland that painted a “benign” picture of its inhabitants (Hooper 184). Austin describes the Irish as hospitable and patient, similar to the stereo card’s narrative of Ireland as “the height of hospitality” and “cream of kindly welcome.” However, this benign picture would not last: nationalist sentiment grew during the turn of the 20th century, erupting violently during the Easter Rising (1916) and subsequent partition and civil war (Austin 185).

Sources and Further Reading:

Adelman, Paul and Robert Pearce. Great Britain and the Irish Question 1800-1922. 2nd ed. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2001. Print.

Hooper, Glenn. “The Isles/Ireland: the wilder shore.” The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing. Ed. Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Print.

Thompson, Spurgeon. “Famine Travel: Irish Tourism from the Great Famine to Decolonization.” Travel Writing and Tourism in Britain and Ireland. 164-180.Travel Writing and Tourism in Britain and Ireland. Ed. Benjamin Colbert. Basingtoke: Palgrave Macmilan, 2012. Print.

Williams, William H. A. “The Irish Tour, 1800-1850.” Travel Writing and Tourism in Britain and Ireland.