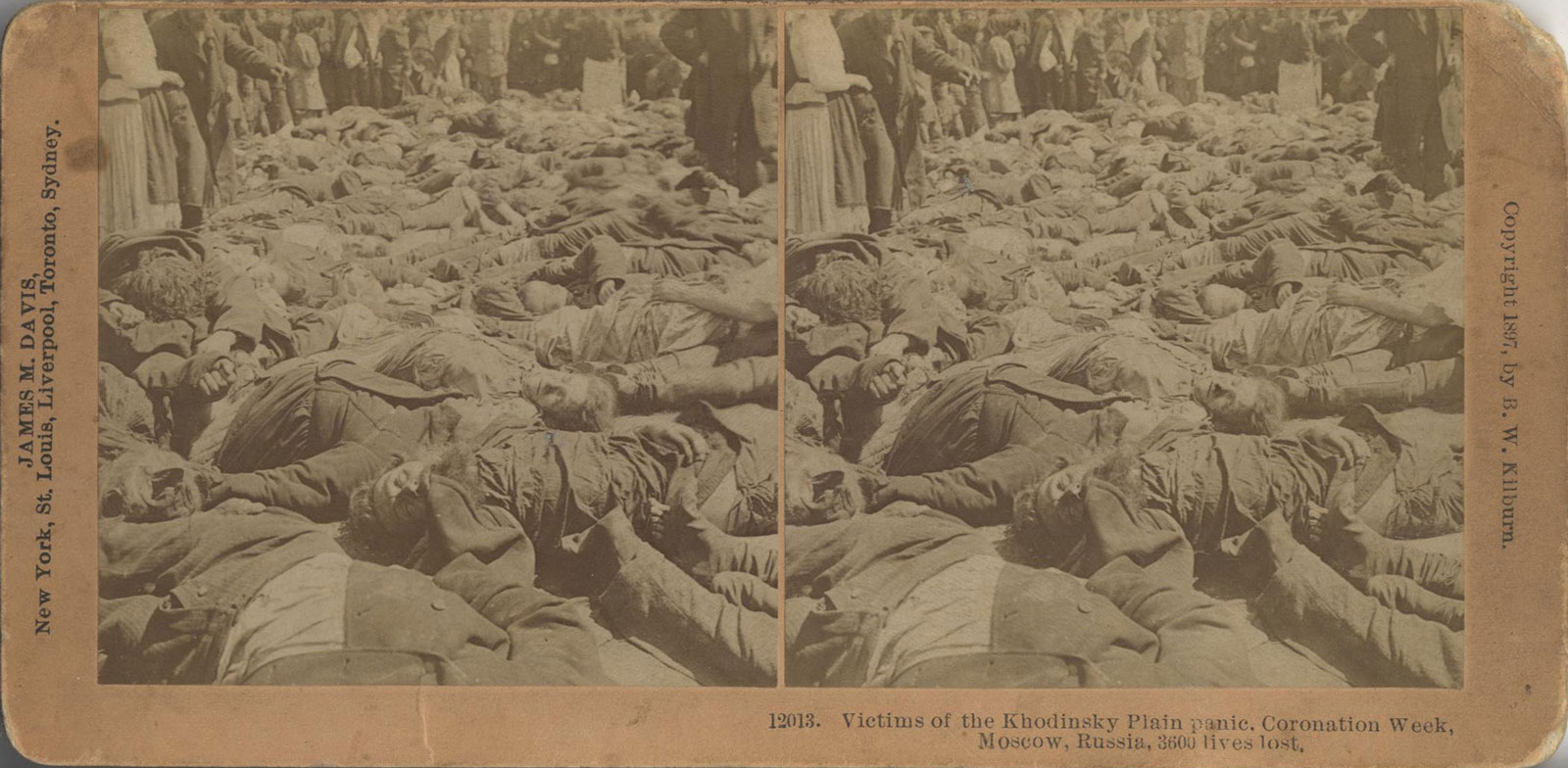

Victims of the Khodinsky Plain panic (1897)

Compared to a different stereograph from the same photographer, this stereograph omits the faces of those standing around the bodies, as well the stalls and sky in the background. Where the former offered some negative space in which to let the eye rest, the latter immerses the viewer while denying any such escape. The three-dimensional effect further enhances this immersion: the way the bodies overlap (a phenomena called occlusion) heighten the illusion of depth when the stereo card is viewed in 3D (Crary 124-5). Thus, the pile of bodies would seem to to recede further and further into the distance, emphasizing their sheer scale in a way that could not be accomplished with 2D photography.

These immersive techniques, when combined with such unpleasant subject matter, seem far from the earlier understanding of stereography as a pleasing, educational, and passive artform for its audience. If the stereograph is “pleasing,” it would not be pleasure in the traditional sense, and one might question whether it would be voyeuristic or sympathetic. If the stereograph is educational, does it seek to educate viewers about a less idealistic side of humanity rather than the cultural and intellectual refinement that David Brewster envisioned? Does the stereograph promote a passive experience that preserves the boundary between viewer and the viewed, or seek to close the gap through immersion?

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1990. Print.

News coverage, both within and outside Russia, concerned itself with the question of responsibility for the event. Although coverage varied in their sympathy (or lack thereof) towards the mob, Baker writes that it was “perhaps, inevitable, in an autocratic regime, that responsibility for any popular disaster would eventually be laid at the door of the authorities that had organised it” (8). Though Western news articles were (at least initially) sympathetic towards Tzar Nicholas II, emphasizing his sorrow and subsequent charitable actions (Sydney Herald; Baker 23), Baker reveals that the Khodynka tragedy and its aftermath shook Russian confidence in royal authority and “provoked the first strains of popular hostility towards Nicholas II” (38-39). Though Nicholas made hospital rounds and attended a special mourning service, he did not cancel his appearance at a ball later that evening — a decision that caused some controversy—though several accounts note that he looked uncomfortable throughout the event (16-19). Some critics and historians interpret this decision as an attempt to appease his family and the foreign dignitaries that had travelled long distances to celebrate his coronation (Baker 19-21; Warth 27-28). The coronation celebration, intended to be “an emblem of future prosperity” (Baker 2), cast a shadow on Nicholas’s reign and remains one of its most memorable events—especially considering his eventual forced abdication and execution following the Russian Revolution.

Sources and Further Reading:

“THE MOSCOW DISASTER. PANIC AT THE FETES. THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE TRAMPLED TO DEATH. TERRIBLE SCENES. [BY TELEGRAPH.] (FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT.) ALBANY, Saturday.” The Sydney Morning Herald 6 July 1896: 5. Web. Available online.

Baker, Helen. “Monarchy Discredited? Reactions to the Khodynka Coronation Catastrophe of 1896.” 16.1 (2003): 1–46. Web. Available online.

Warth, Robert D. Nicholas II: The Life and Reign of Russia’s Last Monarch. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 1997. Print.