Not unlike other migrants, refugees are confronted with new environments – affected by factors such as weather conditions, but also social and economic constraints. Individuals and the community play a significant role in helping refugees to adapt.

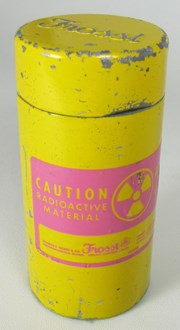

(20) Gleb Paul Krotkov (1901-1968)

Picture: Gleb Paul Krotkov with a tobacco plant in his laboratory at Queen’s, Queen’s Journal, January 10, 1958, p. 5, Queen’s University Archives

Gleb Paul Krotkov was born in Moscow and lived with his family in Southern Russia after the revolution. He fought in the White Russian Navy and fled in 1920 via Tunis and Marseille to Prague, Czechoslovakia. After his studies and a Bachelor of Science degree, Krotkov immigrated to Canada and worked for two years on a farm. He continued his studies and earned a PhD in 1934 at the University of Toronto, after which he was immediately hired by the Department of Biology at Queen’s as a lecturer and specialist in plant physiology.

At Queen’s, in 1948, Krotkov established the first radio-isotope laboratory for biological work in Canada, which utilized isotopes to study intermediary metabolism in plants. Krotkov became the R. Samuel McLaughlin Research Professor of Biology in 1954, was a member of the Royal Society of Canada and awarded the Flavelle Medal in 1964.

As early as January 1933, Krotkov gave a talk to the Levana Society about his experience and “the friendliness of the Canadians towards the foreigners.” However, Kingston and the University provided him not only with a job opportunity. Krotkovs’ childhood friend, Valia, fled the revolution as well, and followed him to Canada where they were eventually married. Valia Krotkov taught mathematics and astronomy at Queen’s and helped start the Department of Russian. Her obituary in the Alumni Review from May 1998 mentioned that both of them “were always thankful to this Canadian city and university which so warmly helped them to build a new life.”

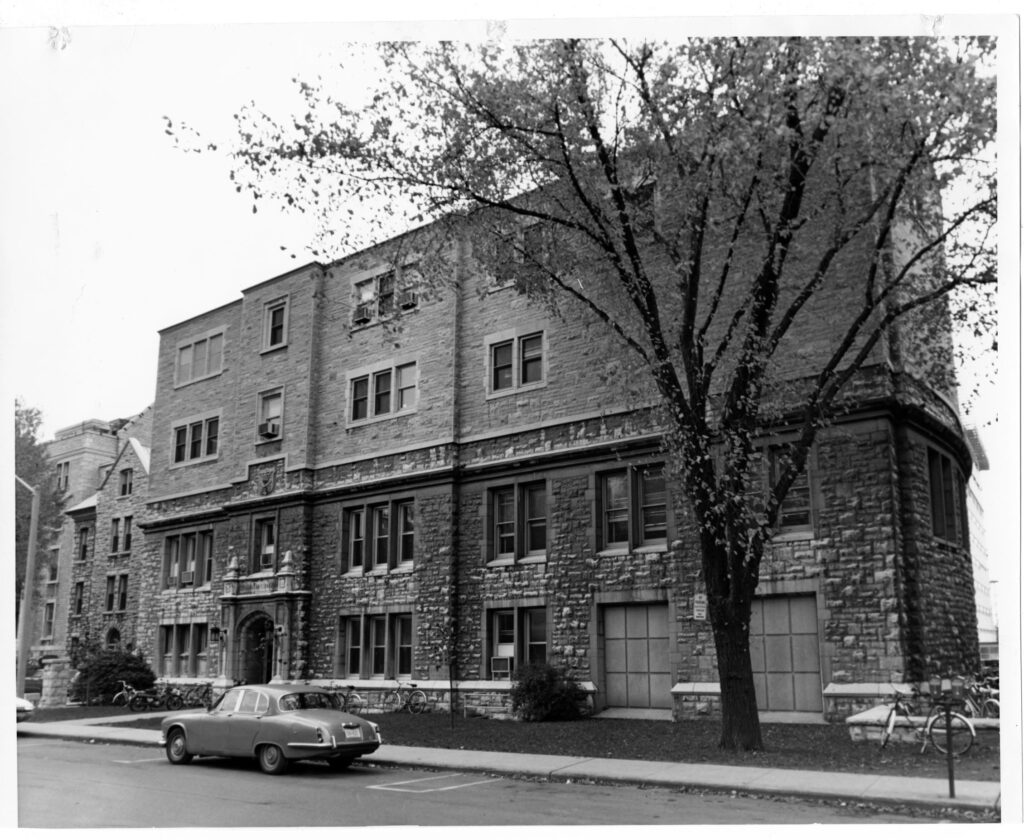

(21) Joseph Abramsky (1857-1927)

Picture: Portrait of Joseph Abramsky, c. 1900, Ontario Jewish Archives, 3320

Joseph Abramsky’s story is one of endearing hard work, success, and community. Born in what is now Belarus in 1857, Abramsky worked as a travelling-salesman within what was known as “The Pale of Settlement” in the Russian Empire. From 1791 to 1917, this area was deemed the only land Jewish residency was permitted within the Empire’s borders, and served as the grounds for numerous pogroms committed against Jewish peoples. In 1890, Abramsky was able to leave from what is now Eastern Poland and travelled to Kingston, where he had familial connections.

In 1891, he opened the Joseph Abramsky Department Store in downtown Kingston at 277 Princess Street which lasted as a staple of the community until 1977. Abramsky reciprocated the relief he originally received from family and in turn provided an avenue for the migration of four of his siblings from Eastern Europe. Abramsky not only made a personal impact in the Kingston community, but also had a generational effect through his son, Harry Abramsky (along with his spouse, Ethel), and their continued support of the local community and Queen’s University through generous donations and financial support. Specifically, Harry and Ethel donated $200,000 over five years during the 1950s to Queen’s for the construction of a specialized facility for physiology research like that by Donald Jennings presented here.

Despite this generous donation, the University did not name the building “Abramsky Hall” or install a plaque outside its doors until 1974, following campaigning by Nate Kaufman and Dr. H. Garfield Kelly (Queen’s MD, 1940). This reflects the reality of Kingston, Queen’s, and Canada in a larger context in relation to immigrants and refugees: namely, that relationships are complex; that many newcomers are still subject to fear, frustration, discrimination, and racism, while simultaneously offering and attempting to inspire positive change, safety, acceptance, and inclusion.

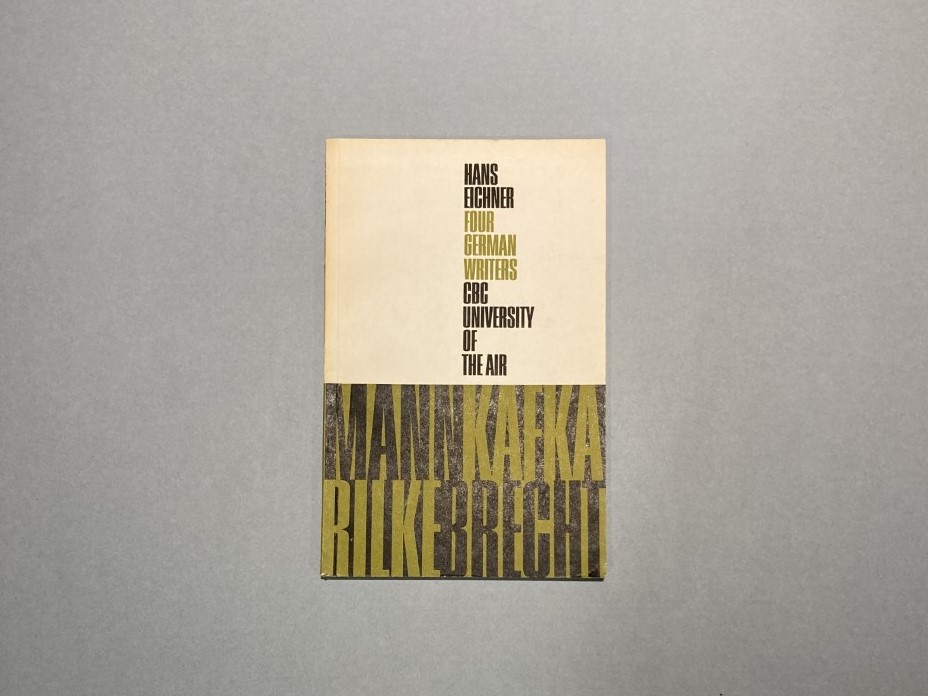

(22) Hans Eichner (1921-2009)

Picture: Hans Eichner (back row, right) with the German Club at Queen’s in the Tricolor ’57 (Kingston: Alma Mater Society 1957), p. 199, Queen’s University Archives

Hans Eichner was the son of a Jewish family from Vienna, Austria. After the Kristallnacht pogrom in fall 1938, he fled with the help of the Jewish Aid Committee to Belgium and later to England. Interned as an ‘enemy alien’ in 1940, Eichner was sent to Australia and started studying in an internment camp. After the war he was a student of German studies at the University of London, England, where he earned his PhD Shortly after, in 1950, he started as a German lecturer at Queen’s University where he immediately fell in love with the landscape. Eichner left Kingston in 1967 and became the chair of the German Studies Department at the University of Toronto.

The book, Four German Writers (1964), illustrates the ambivalence of his arrival: persecuted by German-speaking Nazis, he built his career on this language that was his own. He became a well-known specialist and translator of the philosopher Friedrich Schlegel and a scholar of Thomas Mann. The latter was the focus of Eichner’s PhD thesis and is one of the four German writers introduced in his radio lectures in winter 1963/64. But Mann also had a similar fate to Eichner; the democrat and novelist fled Nazi Germany in 1933. The same is true for Communist dramatist Bertolt Brecht, also introduced in this volume by Eichner.

This intersection of language and culture remained the focus of the Germanist, not only in his research and teaching at Queen’s. In 1957, for example, Eichner read poetry by Rainer Maria Rilke at the German Club on campus, another author introduced in this book. Shortly before his death, Eichner’s semi-autobiographically novel, Kahn & Engelmann, was published in 2000 first in German, addressing his family history, Jewish identity, and the Holocaust. This book shows, in particular, the fragility of a term like “arrival” – and how long the process of arriving can take for refugees.

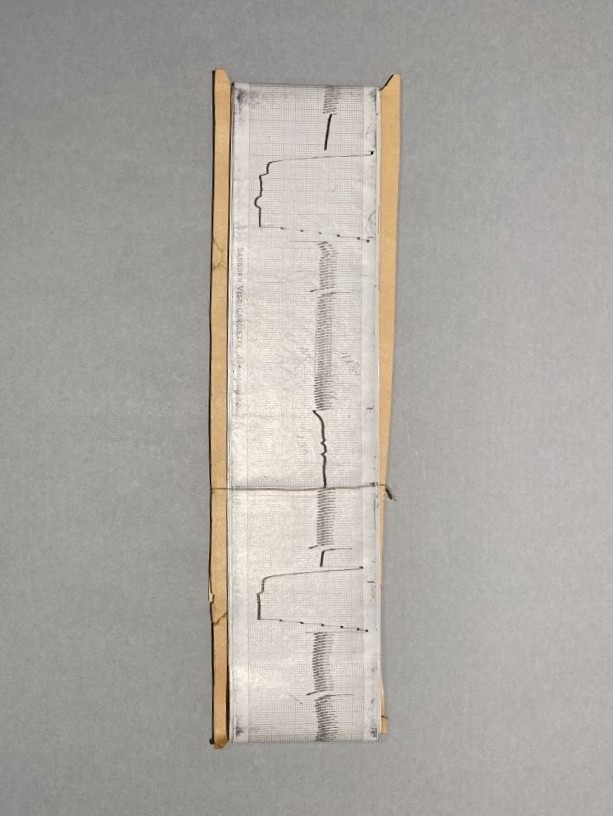

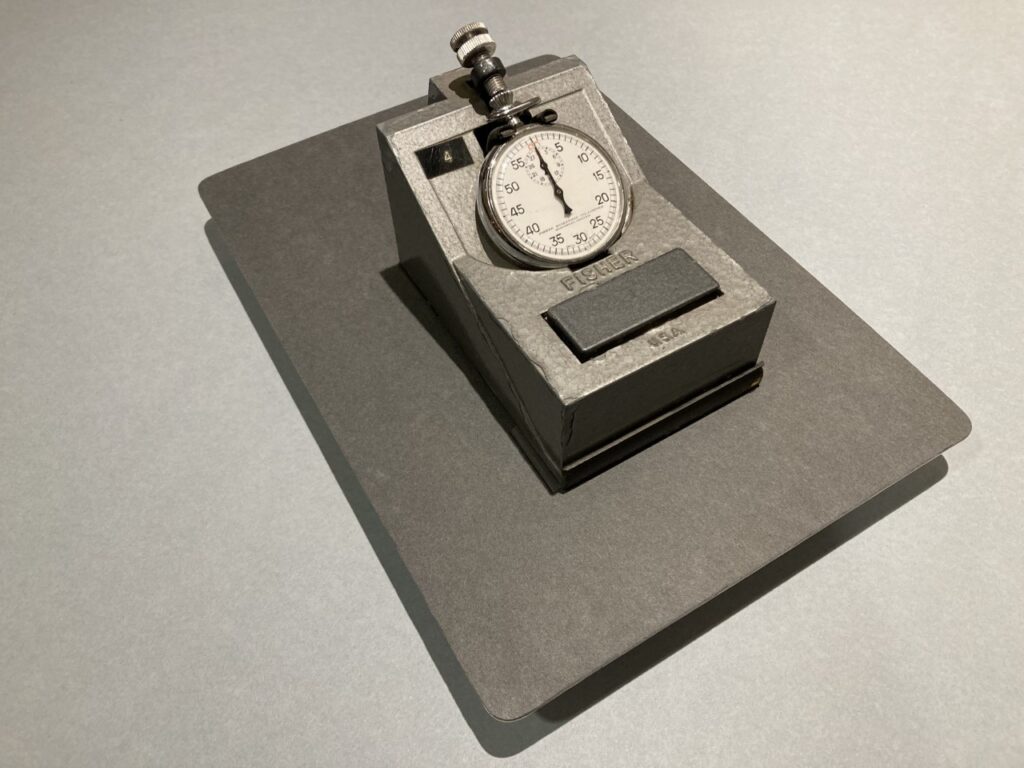

(23) Ödön Kiss (1921-1972)

Picture: View of the front of Richardson Laboratory, 1972, Queen’s Picture Collection, Series S4, folder V28-B-RichL-3, Queen’s University Archives

Born in 1921 in Maglód, Hungary, Kiss was a student at Péter Pázmány University in Budapest in 1949. When the Hungarian Revolution began in 1956, Kiss was forced to leave Budapest due to the suppression of the coup directed at university-educated citizens. His transition to Canada was difficult, as Kiss details how he “wept for ‘Mother Europe’” until he could not cry anymore as his boat sailed past Newfoundland. Kingston for him was meant to be a temporary stop, so he initially kept his head down and followed his own code of behavior for new immigrants: “Silently listen to the noise outside; The racket and the chatting in strange tongues; But be prepared and vigilant inside,” he wrote in his poem “Uzenet az emigrans magyaroknak” (“Message to the Hungarian emigrants”) in 1966.

However he grew to love the city and chose to remain.He worked as a laboratory technologist at the Department of Biology at Queen’s University from 1958 until 1972. In 1960, he published a paper with Queen’s professor George A. Mayer on “Blood Viscosity and in Vitro Anticoagulants” in the American Journal of Physiology. This stop clock from the collection of the Museum of Health Care in Kingston was part of these experiments that were probably conducted in Richardson Laboratory. The connection between the two was a result of origin, Mayer held a medical degree from Budapest, Hungary, and was active in the Citizens Committee for Hungarian Refugees in Kingston in 1956.

In his free time, Kiss published works of poetry about his found city of Kingston, such as A sziget nincs többé, Kingstoni temetés (The Island Is No More, Kingston Funeral, 1972), Átutazóban a városomon: versek (In Transit Through my City, 1970) and also of Hungary, Emlékezzetk Magyarországra! (Remember Hungary!, 1966). Writing under the pen-name, Aladár Visegrádi, he received the Árpád Prize in 1970, and became a member of the Árpád Academy in 1971. Kiss was one of the founders and early secretary of the Canadian Association of Hungarian Writers, an organization that helped connect Hungarian refugee writers to the cultures of both their home and adopted country. He died in Kingston at 51 years old in 1972.

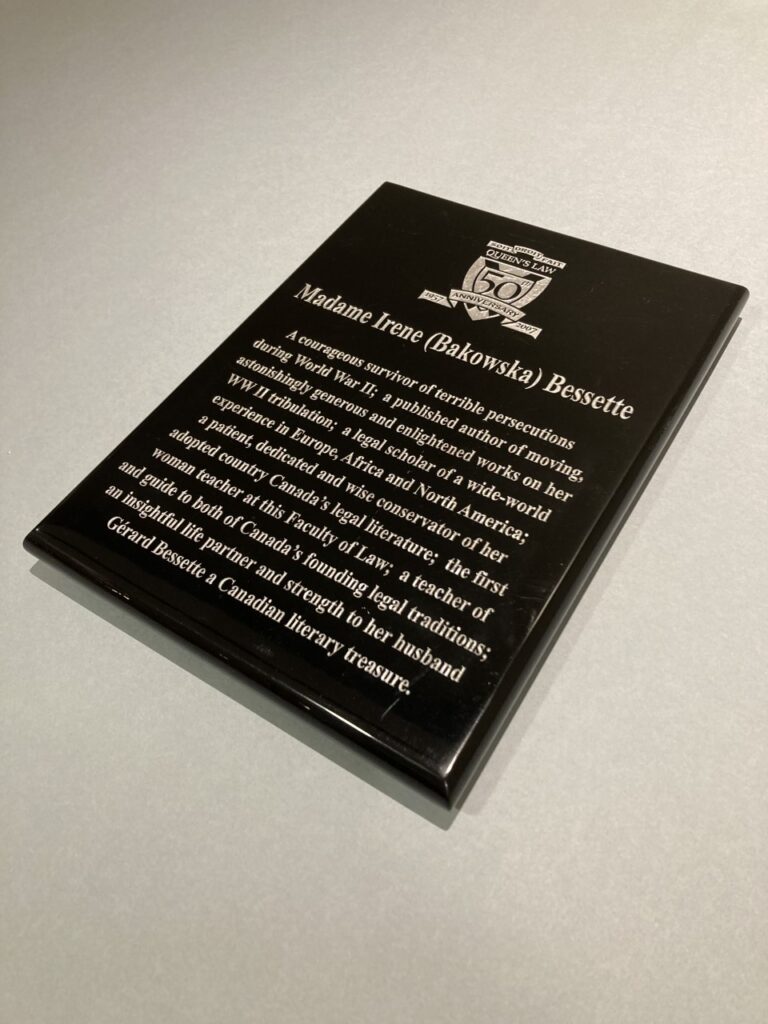

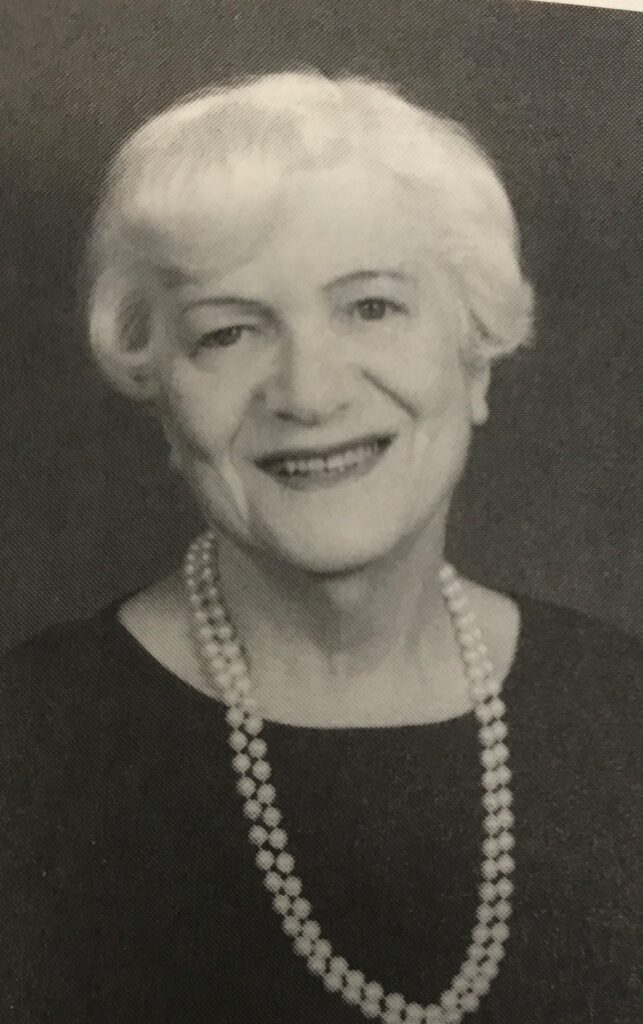

(24) Irene Bessette (1924-2012)

Picture: Irena Bakowksa, in: Irena Bakowska, Not All Was Lost: A Young Woman’s Memoir 1939-1946 (Kingston: Karijan Publishing, 1998)

Born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1924 as Irena Borman, she assumed the name of Irena Bakowska during the Second World War in order to hide her Jewish identity. Irena lived through the bombing of Warsaw, the persecution and murder of Warsaw Jews before their imprisonment in the Ghetto, shared the misery of Polish Christians enslaved to work for the Germans, and witnessed their confusion and hardship when liberated in France. In her own words, “against this historic panorama, I grew from adolescence into womanhood.”

Irena hid her Jewish identity throughout the war, even from her first husband, Józef, a Polish Christian and the father of her child, Richard. Surviving the war, Irena returned to Poland in 1946, but realizing that Jews were no longer welcome there, divorced, and eventually migrated to France, leaving her son in the care of her parents. Heartbroken, she left Warsaw for the last time; the first time was upon her imprisonment in the Ghetto, the second was upon her deportation for slave labour on a German farm in Lorraine, but it was this final loss in liberated Poland that she considered the most painful and unwarranted. Rebuilding her life in France, Irena eventually reunited with her family in the United States. Looking back on her early life in a 1998 memoir, Not All Was Lost, Irena observed that the ethnic and religious intolerance and political unrest that forces people to leave their country “may inflict as much pain as the onslaught of war or enemy occupation.”

Reclaiming her Jewish identity, Irena was educated in France as a lawyer at Bordeaux. She migrated to the United States in 1955, where she continued her studies in law and as a librarian. She was admitted to the New York Bar in 1966, practiced in Casablanca, was admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1970, and the Law Society of Upper Canada in 1985. Irena came to Queen’s as Law Librarian and Associate Professor of Law in the spring of 1968. Identifying then as Irene Borys, she was Head Law Librarian, taught courses in Quebec civil law, and was the first woman to join the Faculty of Law. At Queen’s she met and married French Studies Professor, Gérard Bessette, whom she described as the first person with whom she felt “complete” and “normal” since the Holocaust. Irene had a prestigious career at Queen’s, where she participated in Jewish life on campus and spoke and published about her experience of the Holocaust; she retired in 1989. Upon the 50th anniversary of the Queen’s University Faculty of Law in 2007, Irene Bessette’s contributions were commemorated with this plaque, normally on display in the Lederman Law Library.

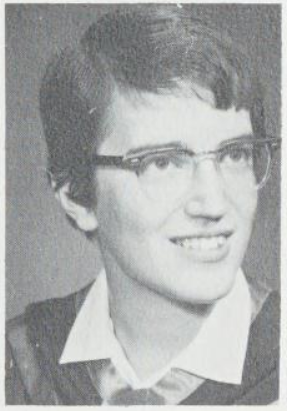

(25) Agnes M. Herzberg (born 1950)

Picture: Agnes M. Herzberg in the Tricolor ’61 (Kingston: Alma Mater Society 1961), p. 23, Queen’s University Archives

Agnes Herzberg’s story begins prior to her birth. Her parents, Luise and Gerhard Herzberg were Jewish German nationals and fled Nazi persecution. They travelled in 1935 to Canada with the financial support of the Carnegie Foundation and Gerhard took up a guest professorship position at the University of Saskatchewan. In 1936 they had their first child, Paul Herzberg, and continued their academic careers.

Academics would be a major foundation for all of the Herzberg family, with Gerhard winning the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1971, Luise’s astrophysics work gaining sizeable recognition in the 1960s, and Paul who dedicated his life to education as a member of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics and authored a memoir about his mother, highlighting her accomplishments as an astrophysicist and the challenges she faced as the wife of a world-famous scientist.

Agnes Herzberg was born in Saskatoon in 1940, as a child of refugees in the second generation. She left Saskatchewan and attended Queen’s University for her undergraduate degree in 1961 before returning to Western Canada for her MA. Over the next few decades she made numerous contributions to the fields of statistics and mathematics, in particular regarding their contributions to the design of clinical trials in medicine. One example of her work is a co-authored paper examining the properties of the Sudoku puzzle, including its potential for data compression. Finally, since 1996, Dr. Herzberg has organized the annual Conference on Statistics, Science and Public Policy.

The group selects topics ranging from science, public policy, education, risks, ethics, health, globalization, and democracy for discussion among a selected group of scientists, policy makers, journalists, heads of regulatory agencies, and other influential participants. She also took responsibility for editing and publishing the conference proceedings to inform public policy and in turn potentially improve the lives of individuals who are in a similar position as her parents.

(26) Alaa Khalaf (born 2002)

Picture: Alaa Khalaf, 2021

Born in Syria in 2002, Alaa rose above many obstacles to find a new home in Toronto, and at Queen’s University. She writes that “I have only known the vibrant and beautiful city of Damascus up until the noise of the famous street markets started diminishing, and up until Syrians started dying.”

Alaa describes how life became blurry as her family left their house in Syria, and faced four years of displacement before arriving in Toronto in 2017. She challenged herself to learn English in three months, and dedicated herself to helping newcomers in her high school. In Grade 12, she was one of thirty-six students from across Canada to be awarded a 2020 Loran Scholarship – an award that goes beyond just grades, recognizing merit, potential, character, and courage. Loran took notice of Alaa’s desire to get involved and give back to the communities that welcomed her and her family. Alaa expresses that “being able to attend University is a dream for many but attending Queen’s University as a Loran Scholar is a privilege. Having a safe home and a supportive family is a privilege. Being a refugee taught me not to take anything for granted and to recognize the many privileges that we have that are a dream for others.” Enrolled in the Bachelor of Nursing program, Alaa describes that while her initial move to Kingston was difficult, after finally settling in Toronto, the small city energy of Kingston reminds her of her hometown in Syria.